Finally after years of criticism, Facebook announced that it would stop allowing advertisers in key categories to show their messages only to people of a certain race, gender or age group. The company said that anyone advertising housing, jobs or credit — three areas where federal law prohibits discrimination in ads — would no longer have the option of explicitly targeting people on the basis of those characteristics.

Facebook has been accused of allowing advertisers to unlawfully discriminate against minorities, women, and the elderly by using the platform’s ad-targeting technology. The settlement resolves five separate cases that had been brought against Facebook over discriminatory advertising since 2016, following a ProPublica investigation that revealed Facebook let advertisers choose to hide their ads from blacks, Hispanics, or people of other “ethnic affinities.” Lawsuits soon followed. The most recent case was an EEOC complaint by the American Civil Liberties Union in September, alleging that Facebook allowed job ads to discriminate against women.

This is significant because Facebook’s massive revenue primarily comes from ads, which are so lucrative because of their microtargeting capabilities. In 2017, according to its annual earnings report, the company made $39.94 billion on ads alone. Its total revenue for that year was $40.65 billion, meaning ads accounted for roughly 98% of revenue.

But when a company or advertiser shows an ad only to certain people, it excludes a protected class of workers. And that’s illegal under federal law. “It is a game-changer,” says Lisa Rice, the executive vice president of the National Fair Housing Alliance, whose lawsuit against Facebook was among those settled Tuesday. “The settlement positions Facebook to be a pacesetter and a leader on civil rights issues in the tech field.”

“We think this settlement is historic and will go a long way toward making sure that these types of discriminatory practices can’t happen,” Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s COO, said in an interview.

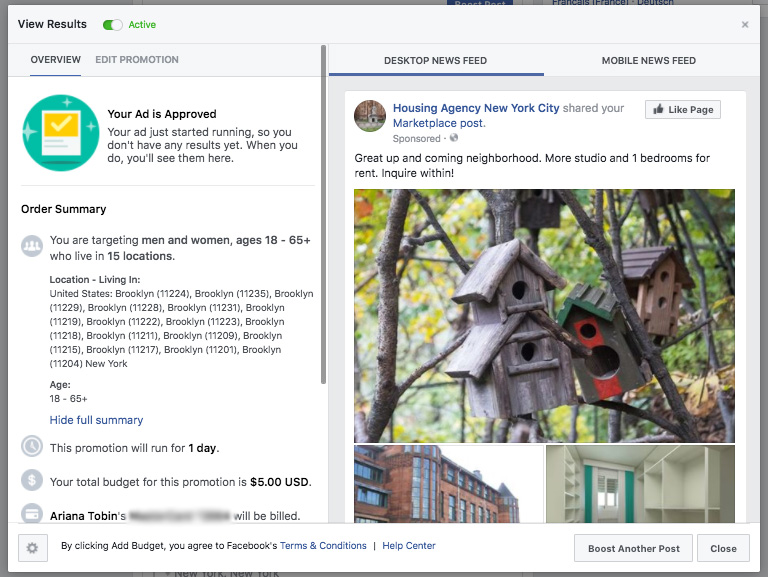

As part of the agreement, Facebook will build a designated portal for advertisers to create housing, employment, and credit ads, which will not allow targeting users by age, gender, zip code, or other categories covered by anti-discrimination laws. Microtargeting options that appear to relate to these protected categories will be off-limits as well. Any advertiser that wants to run an ad on Facebook will be required to indicate if their ad is related to one of these three things. According to The Washington Post, Facebook has said it will make these changes by the end of the year.

“Housing, employment, and credit ads are crucial to helping people buy new homes, start great careers, and gain access to credit. They should never be used to exclude or harm people,” Sandberg wrote in a post announcing the settlement. “Getting this right is deeply important to me and all of us at Facebook because inclusivity is a core value for our company.”

Advertisers that deliberately and repeatedly avoid the new portal when placing ads in the three regulated areas will probably face consequences, though the company said it had yet to determine those.

Pauline Kim, a professor of employment law at Washington University in St. Louis, praised the changes but cautioned against overstating their significance. “Taking the explicit ability to discriminate off the table is an important first step,” Professor Kim said. “But I don’t think it solves the problem of the potential for biased serving of ads.” Ms. Kim said, for example, that an employer could place an ad that it intended to show to both men and women, but over time, Facebook’s algorithms could begin to show the ad primarily to men if it determined that men were much likelier to click on the ad. “It’s within the realm of possibility depending on how the algorithm is constructed,” Professor Kim said. “You could end up serving ads, inadvertently, to biased audiences.”

Sandberg acknowledged the limits of the policy changes and said Facebook had committed to working with the other parties to find additional ways to root out discrimination. The parties will discuss progress on that front every six months for three years after the changes are rolled out.

“In addition to being a historic settlement of five separate lawsuits that will change practices on Facebook and other platforms, it’s also notable that we agreed to continue to study the algorithmic effect of ads with Facebook,” said Anthony Romero, executive director of the A.C.L.U.

Facebook is also removing thousands of so-called interest segments, including some that advertisers could use to reach people by characteristics like gender or age, for ads in the three regulated areas. For example, to show how advertisers could keep certain groups from seeing housing ads on Facebook, the National Fair Housing Alliance once created a fictitious ad that excluded groups like “corporate moms” and “stay at home” mothers.

Those segments would no longer be available for targeting by housing, employment and credit ads once Facebook carries out the proposed changes.

Despite some of the expected pushback, civil rights advocates are applauding and they are confident Facebook will follow through. The company has agreed to twice-annual meetings with the groups, as well as ongoing trainings with outside experts on these issues. Facebook has agreed to let the NFHA, the ACLU, and others conduct independent testing of its ad sites to make sure Facebook does what it says it will.

“If any advertiser was trying to skirt or circumvent the system, we have methods for finding that out and we’ll be able to bring that to the attention of Facebook,” says Rice of the National Fair Housing Alliance.