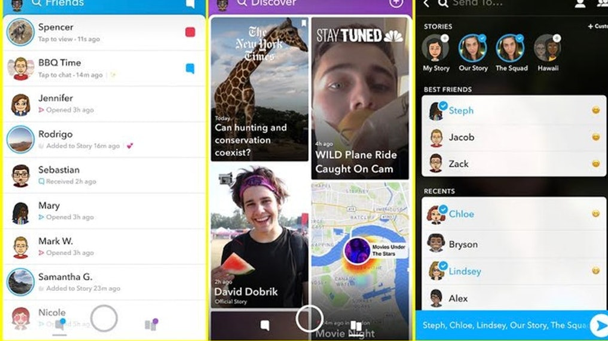

Snapchat gained success soon after its launch due to its one of a kind feature. No matter what type of snap you post, no one could take a screenshot or save it without your knowledge. If you post a picture on your Snapchat account, it stays there for a good 24 hours and then it’s deleted. This feature empowers kids and teens to do and share whatever they want on Snapchat, without fearing to be caught. Which has parents concerned about the safety of their kids.

With users of all ages, it’s risky to let young kids and teens use a social networking app without keeping a check on their activities.

Unfortunately for parents, Snapchat does not provide a feature to view snapchat stories without the user knowing. Your account is protected as long as you have a unique password, are careful who you snap with, and you don’t reveal too much personal information.

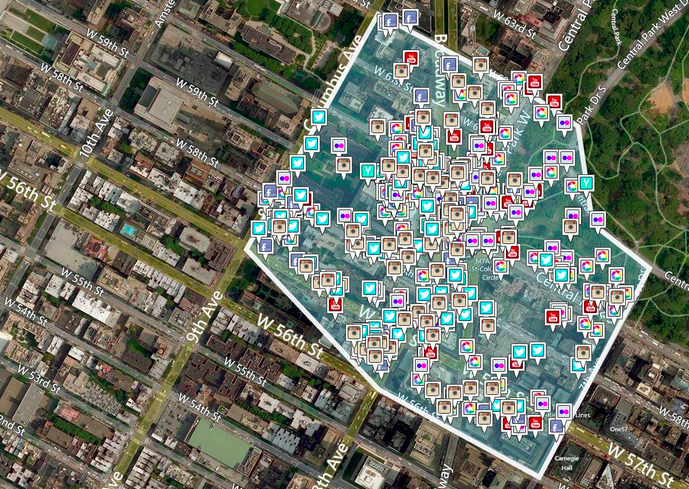

But what many folks do not know that there now are multiple ways to spy on snapchat of anyone. Snapchat’s Built-In Spy Feature, Snap Map, gives you an opportunity to spy on your friends and know their location. Many users have probably come across this feature, but you might not think of using it as the Snapchat spy tool.

Snap Map displays information about all your friends who were lately available on Snapchat, and have shared their location with you. If you want to spy anyone or wish to surprise your friends by joining them randomly at a particular spot, Snap Map assists you by showing the recent movements of your friends. Activating this built-in snapchat spy feature is easy to do, would take just a couple of taps from your fingers.

If you want to be a little more incognito when spying, there are several apps available:

SpyAdvice tops all the other spying apps due to its exciting features. You can see complete tracking of all multimedia sent and received via Snapchat, view exact time of sharing of all photos and videos, access deleted media, see a record of recent keystrokes, and have real-time location monitoring with GPS tracking. SpyAdvice is not just a spying app; it is a complete package that enables you to hack someone’s snapchat without them knowing – and get access to every single activity of the user.

If you prefer a free option, checkout Snapch. This spying tool uses various VPNs which entirely masks your presence. Your targeted user will never doubt any external access to its Snapchat activities. Through Snapch, you can freely get your target users snap stories, chat logs, and even login information. This empowers you to get instant access to your target’s Snapchat account instantly without any spy app.

Another option is Snapchat Photo Grabber. Though this tool is not as smart as the others, particularly the SpyAdvice, you can still use it as a quick option to access anyone’s Snapchat account. This handy tool will let you access your target’s snapchat account within minutes.

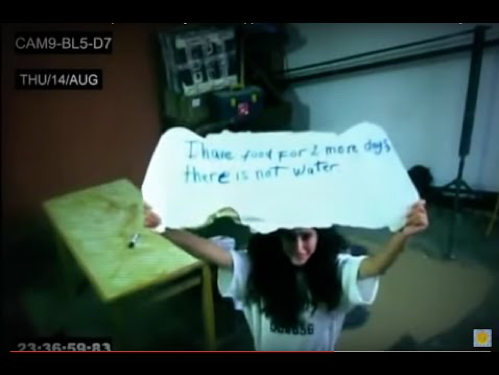

Although spying is constantly being debated as legal or illegal, sometimes it’s more important to get involved in order to protect your loved ones from bullies, predators, or criminals. Obviously no one is going to share their secret activities with you, therefore, you have a reason to spy on the Snapchat account of anyone you doubt or want to keep protected online. If you wish to protect your child as a worried parent, desire to keep an eye on your spouse, or want your staff to be sincere with their work instead of wasting time on Snapchatting – then it indeed is your right to spy their Snapchat accounts.

About Us:

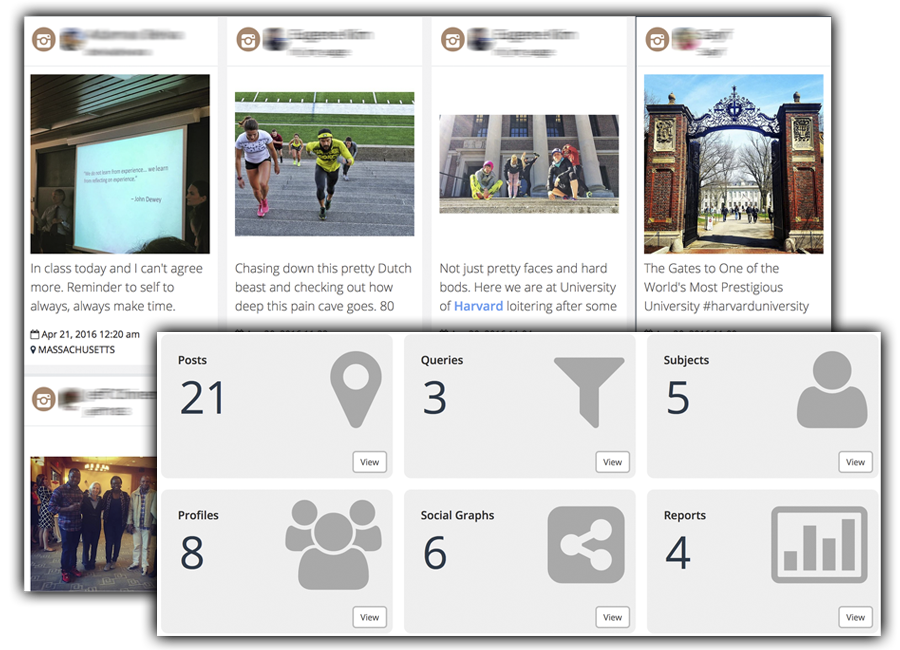

We have been mining social media since 2007 for our clients. By utilizing best in class software programs, we offer a service called eChatter.

eChatter works with you to obtain your objectives in a fast, accurate and reliable facet. By keeping our strengthened principals, yet evolving with this industry, we lead in social media monitoring. Since 2007, we have been dedicated to providing our customers with the most authentic data.

We offer:

• Deep Web Scans

• Jury Vetting

• Jury Monitoring

• Quick Scan

www.e-chatter.net

(866) 703-8238