The best VPNs, or virtual private networks, can help secure your web traffic and protect you from anyone who wants to steal or monetize your data.

Think about how much information about yourself you transmit over the internet. Frightening isn’t it?

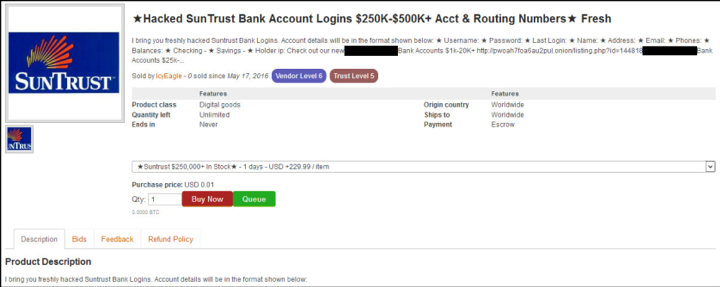

Now think about the safety measures you have put in place to protect your information? Do you feel a sense of panic? That’s completely normal considering the amount of hackers, spies, and thieves trying to gain access to your personal data.

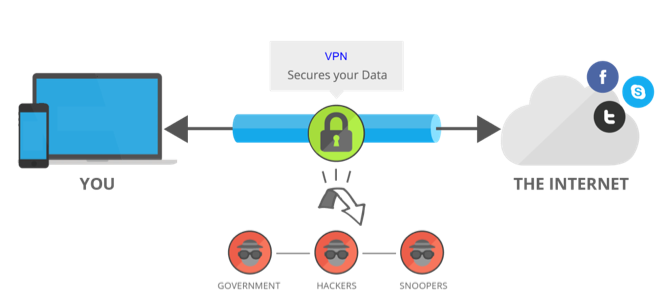

One of the best ways to protect yourself is to use a virtual private network (VPN). A VPN creates a virtual encrypted tunnel where all of your internet traffic is routed through, securing your data from prying eyes. Best of all, your computer appears to have the IP address of the VPN server, masking your identity and location. When your data reaches the VPN server, it exits onto the public internet. If the site you’re heading to uses HTTPS to secure the connection, you’re still secure. But even if it was intercepted, it’s difficult to trace the data back to you, since it appears to be coming from the VPN server.

Let’s think of some specific scenarios in which a VPN might be useful.

1) Consider the public Wi-Fi network…at your favorite coffee shop, local mall, or airport. You connect to their Wi-Fi without a second thought. But did you ever stop to think who might be watching the traffic on that network? How can you be sure the Wi-Fi network is legit? Think about the passwords, banking data, credit card numbers, and private information you transmit every time you go online. Keep in mind that just because it’s called Starbucks_WiFi doesn’t mean it’s really owned by them. There are snoopers everywhere trying to access your information.

Now, If you connect to that same public Wi-Fi network using a VPN you can rest assured that no one on that network will be able to intercept your data.

2) Another concern regarding internet security is related to two groups: the NSA and your ISP.

The NSA’s surveillance tool is massive and at one point had the ability to intercept and analyze just about every transmission sent over the web. But when using a VPN, your data is encrypted and less directly traceable back to you. This doesn’t make you invisible, your traffic and information could still be intercepted. But a VPN adds a layer of encryption during parts of your online traffic’s journey.

Your ISP may already be involved in spying operations, using information about you to fuel the growth of companies like Facebook and Google. Those companies are able to gather huge amounts of data about users, and then use it to target advertising or even sell that data to other companies. ISPs are now allowed to bundle anonymous user data and put it up for sale.

“ISPs are in a position to see a lot of what you do online. They kind of have to be, since they have to carry all of your traffic,” explains Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) senior staff technologist Jeremy Gillula. “Unfortunately, this means that preventing ISP tracking online is a lot harder than preventing other third-party tracking—you can’t just install [the EFF’s privacy-minded browser add-on] Privacy Badger or browse in incognito or private mode.”

What Your VPN Can’t Do

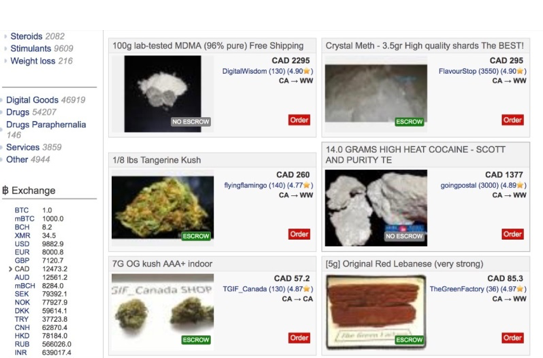

VPNs can only do so much to protect your online activities. If you really want to browse the web anonymously, you’ll want to use Tor. Unlike a VPN, Tor bounces your traffic through several server nodes, making it much harder to trace. It’s also managed by a non-profit organization and distributed for free. Some VPN services will even connect to Tor via VPN, for additional security.

If you do decide to get a VPN, do your homework. A recent investigation into 115 of the world’s most popular VPN services revealed that many are negating their stated claims. To build trust, providers make promises not to track users through logs or other identifying information. The Best VPN recently revealed that 26 out of the 100 biggest VPN services are collecting files that could contain personal and identifying information — things like your IP address, location, bandwidth data, and connection timestamps.

Also consider the other devices you use to access the internet. Smart home devices and phones can’t run VPNs. So the solution would be to install a VPN on your router. This encrypts data as it leaves your home network for the world wild web. Information sent within your network will be available, and any smart devices connected to your network will enjoy a secured connection.

Ultimately, it is up to individuals to protect themselves. Antivirus apps and password managers go a long way toward keeping you safer, but a VPN is a uniquely powerful tool that you should definitely. Whether you opt for a free service or even go all-in with an encrypted router, having some way to encrypt your internet traffic is critically important.