Nextdoor, Citizen, and Amazon Ring…these are the apps responsible for what used to be called “citizen’s arrest”. These apps, which allow users to view local crime in real time and discuss it with people nearby, are some of the most downloaded social and news apps in the US, according to rankings from the App Store and Google Play.

While it’s important to know what is going on in your community, and more specifically, your neighborhood, has it made us paranoid that everyone is out to get us?

Before you download these apps, let’s look at the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Nextdoor

According to the website, Nextdoor is “the best way to stay in the know about what’s going on in your neighborhood—whether it’s finding a last-minute babysitter, learning about an upcoming block party, or hearing about a rash of car break-ins. There are so many ways our neighbors can help us. We just need an easier way to connect with them.”

When I first learned about Nextdoor, I thought, all I need is another app on my phone. And I actually avoided it for a while. But after seeing multiple neighbors post comments, questions, and suggestions, I decided I might as well give it a try.

Most of the posts involve recommendations for lawn care, home maintenance or repair, local hotspots, missing pets, and the like. But more recently there have been a string of posts regarding robberies, break-ins, and more alarming incidents such as lurkers at a local playground.

While I appreciate being kept abreast of everything going on in our community, is it making us so leery and suspicious that we assume everyone has negative intentions?

In the US, Nextdoor has worryingly been accused of being a hotbed of racial profiling and bigotry, having been called out by the black news and opinion site The Root for the way users report people of color in their neighborhood as being suspicious.

But there is a silver lining in all of this…Nextdoor residents are quick to help one another in times of need. During the recent Hurricane Dorian event, one post from the Nextdoor app by a resident of the “Cork Vicinity” of Central Florida reads—“Anybody know where there’s water?” In less than 23 hours more than 50 helpful neighbors recommended 28 nearby neighborhoods where water might be found and encouraged other creative solutions like filling up five gallon buckets with tap water, and even catching and purifying rainwater.

Citizen

Citizen, which was previously titled Vigilante, encourages users to stop crimes in action…by sending 9-1-1 alerts for crimes happening nearby. It also allows users to livestream footage they record of the crime scene, “chat with other Citizen users as situations develop” and “build out your Inner Circle of family and friends to create your own personal safety network, and receive alerts whenever they’re close to danger.”

According to their website…”Our mission is to keep people safe and informed. We believe everyone has the right to know what’s happening inside their communities in real time, and that transparency can drive change for the better. Citizen users are empowering the city of the future, building new ways to bring people together, creating a safer world, and democratizing 911.”

Amazon Ring

Amazon has recently thrown its hat in the ring — with Ring. It recently advertised an editorial position that would coordinate news coverage on crime, specifically based around its Ring video doorbell and Neighbors, its attendant social media app. Neighbors alerts users to local crime news from “unconfirmed sources” and is full of Amazon Ring videos of people stealing Amazon packages and “suspicious” brown people on porches. “Neighbors is more than an app, it’s the power of your community coming together to keep you safe and informed,” it boasts.

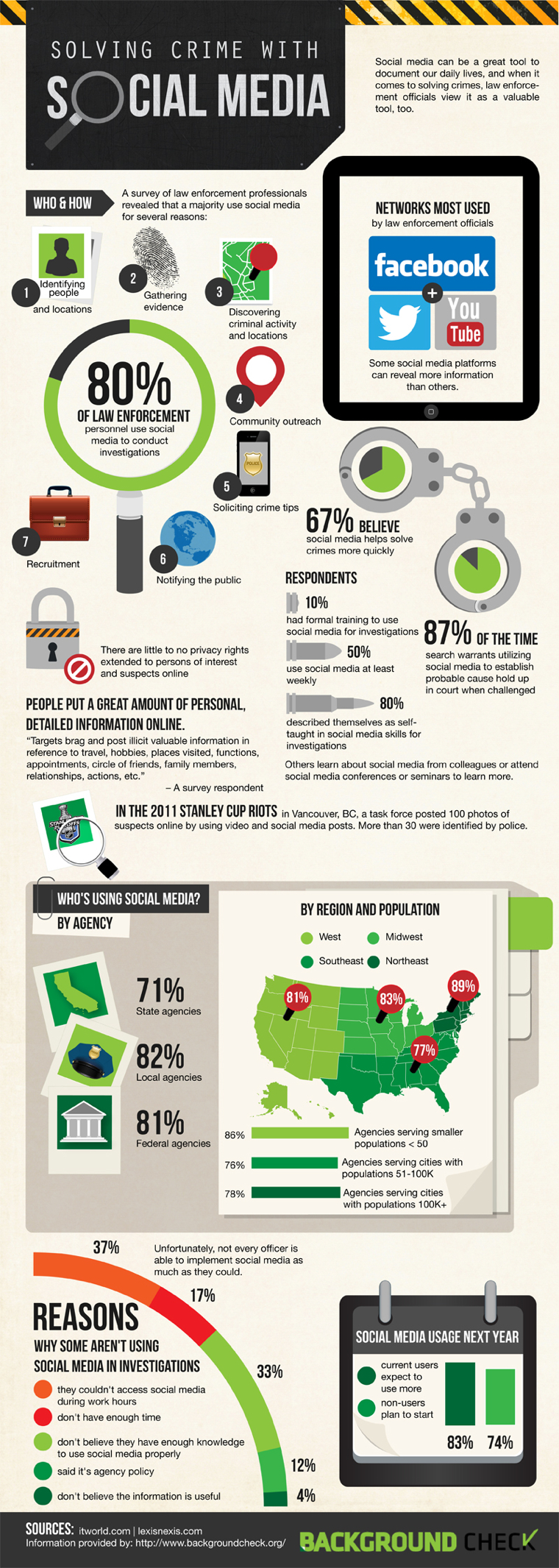

New Found Fear

It’s natural for people to want to know more about the world around them in order to decrease their uncertainty and increase their ability to cope with danger,” says David Ewoldsen, Professor of media and information at Michigan State University. “You go on because you’re afraid and you want to feel more competent, but now you’re seeing crime you didn’t know about,” Ewoldsen said. “The long-term implication is heightened fear and less of a sense of competence. … It’s a negative spiral.”

“Focusing on these things you’re interpreting as danger can change your perception of your overall safety,” Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center, told Recode. “Essentially you’re elevating your stress level. There’s buckets of research that talks about the dangers of stress, from high blood pressure to decreased mental health.”

These apps are particularly scary since they’re discussing crime nearby, within your neighborhood or Zip code. And the issues are compounded by the media, Ewoldsen says. “If you see more coverage of crime you think it’s more of an issue, even if real-world statistics say it isn’t,” Ewoldsen said.

What do we do about it?

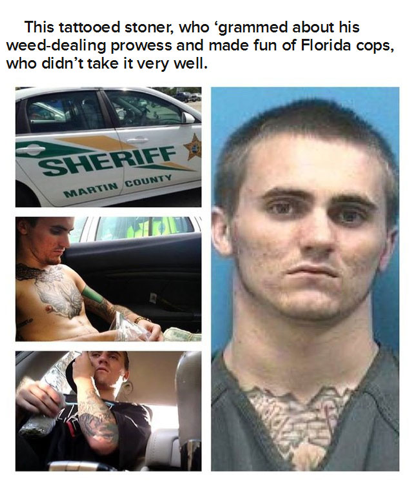

[ctt template=”4″ link=”fnfg3″ via=”no” ]“We need to pay attention and to be more mindful in our consumption of the news,” he said. Turn off notifications for crime that’s not happening around you. Research or read respected sources of news before jumping to conclusions. Be aware of how other people’s biases and those of their fellow app users could skew reporting and the reaction to that reporting.[/ctt]

“It would help if they eliminated all unverified reports,” Rutledge said. In practice, however, this would mean having to verify crimes before they could be posted, which would be very difficult if not impossible.